PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability

Por um escritor misterioso

Descrição

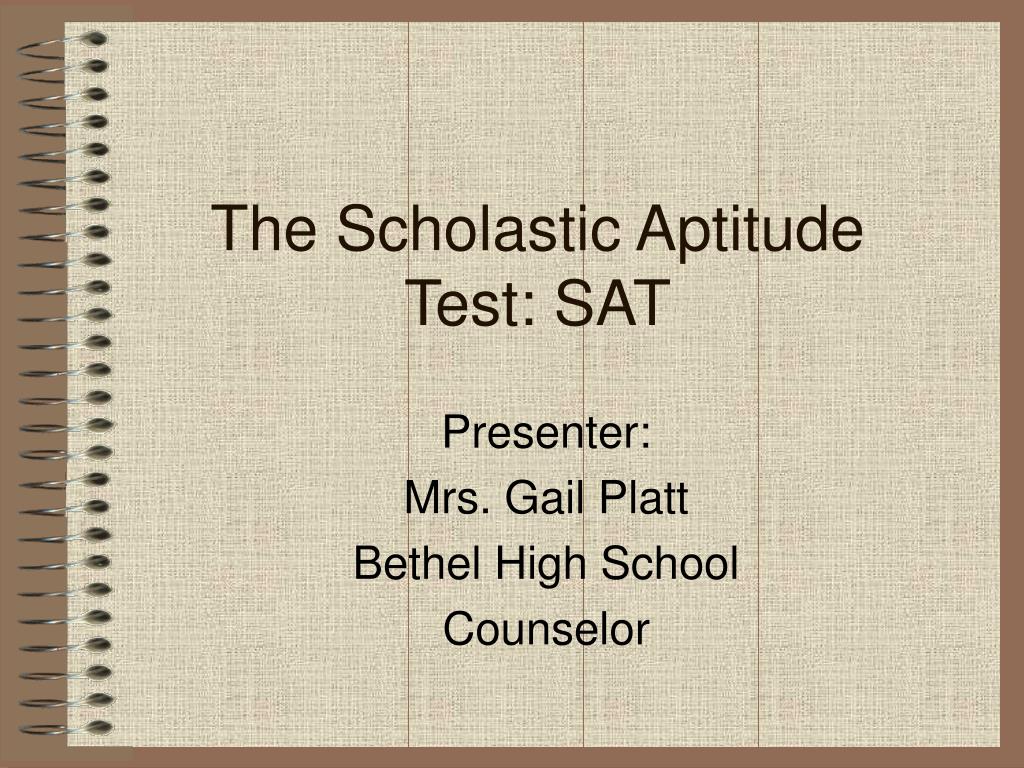

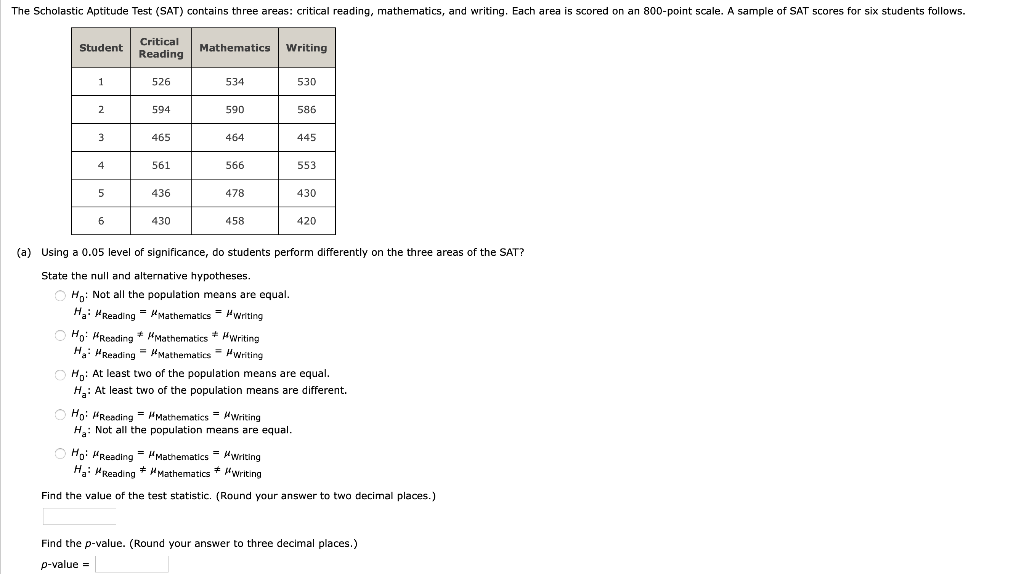

Åsa Mäkitalo and Sven-Eric Reuterberg, WHO TAKES THE SWEDISH SCHOLASTIC APTITUDE TEST? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability. ISSN 0282-2156 Number of pages: 24 The gender differences in SweSAT scores in favour of male test takers have been the subject of a rather intense public debate in Sweden during the last few years. Normally, these differences have been interpreted as a consequence of bias in the test. However, an alternative explanation might well be that the differences in test scores are caused by differential selection effects, which implies that the male and the female test takers are not comparable. In this study the differential selection effects to the SweSAT are studied for a nationally representative sample of male and female test takers born in 1972. The selection effects are measured by test scores, scores on standardized achievement tests and grades from the compulsory school. According to all these variables the male test takers are more strongly selected to the SweSAT than are the female test takers. That is to say that the differences between test takers and others in all of these variables are greatest among men. To some extent, these differential selection effects are the result of men being more variable in all the respects studied. A statistical method has been developed for keeping this difference in variability under control. This control implied that the differential selection effects were reduced for some of the variables up to nearly 50 per centbut still the male test takers were more positively selected. Then, another control variable was introduced, namely previous education measured by the programme chosen in upper secondary school, and the differential selection effects were studied separately for those who had finished a theoretical upper secondary programme and for those who had not. When introducting this control variable the differential selection effects disappeared within the theoretical group, but within the nontheoretical group the male test takers remained more positively selected. Since the great majority of the SweSAT takers belongs to the theoretical group, the results show that the differential selection effects to the SweSAT are mainly due to the differential selection in the transistion from compulsory school to upper secondary school. Furthermore, it has been shown that even if differential selection effects must be taken into consideration when comparing self selected groups, they cannot by themselves explain the group differences in SweSAT scores. Also the differences in the unselected group have to be taken into consideration before claiming bias in the SweSAT. INTRODUCTION Admission tests for entrance into higher education tend to show gender differences in results favouring males. On the Scholastic Assessment Test (SAT) the gender difference on the mathematical part amounts to about half a standard deviation unit. Up to 1972 the verbal part showed differences in the opposite direction, but since then males have outperformed females even on the verbal sections (Wilder & Powell, 1989). The Swedish counterpart to SAT, the Swedish Scholastic Aptitude Test (SweSAT) has shown gender differences in favour of males ever since its introduction in 1977. However, these differences were rarely the subject of any public debate, mainly because the test used to play a limited role in selection to higher education. Only adult applicants, namely, were allowed to take the test. In 1991 the test was given a much more important role as an alternative selection instrument to the leaving certificate from upper secondary school among all applicants. The new role of the SweSAT resulted in a dramatic extension of its use and the gender differences in scores were discussed more intensely. The SweSAT contains six time limited subtests. Three subtests are verbal (Vocabulary, Reading comprehension, English reading comprehension), two are more quantitative (Data Sufficiency and Diagrams, Tables and Maps) and one is a test of general knowledge (General information). All items are in the format of multiple choice and the total SweSAT score is the sum of the number of correctly answered items. A more comprehensive presentation of the SweSAT, its content and history is given by Wedman (1994). Up to 1992 the gender differences amounted to 8 points out of a maximum of 144 items (See Stage, 1985; 1988; 1990; 1992). In 1992, when a test of Study Techniques was replaced by the English reading comprehension test, the difference amounted to 10 points out of a total of 148, which corresponds to about half a standard deviation unit (Ingerskog & Stage, 1993). The greatest gender differences in favour of males have always been found on the more quantitative tests Data Sufficiency (DS) and Diagrams, Tables and Maps (DTM), which is in accordance with earlier studies of results on mathematical tests (Hyde, Fennema & Lamon, 1990). In standardized mean differences the gender difference amounts to approximately 0.60 through 0.70 on these tests. However the gender differences go in the same direction also for all the other subtests even if they are smaller on the verbal parts, about 0.20 0.25 on the Vocabulary and Reading comprehension tests and about 0.40 on the English reading comprehension test. As stated by Wilder & Powell (1989) the gender differences on admission tests may be regarded in different ways. They may be regarded as real, and if so the problem is to identify the underlying mechanisms. Another way is to regard them as artifacts of differential treatment of men and women in society. A third way is to question their existence by claiming bias in the test, differential selection of test takers or statistical effects. Wilder & Powells' review of possible causes of the gender differences show that biological, social, psychological and educational explanations have been considered. Biological explanations have mostly been addressed to differences in spatial ability and the explanations often focus on genetic and chromosomal determinants, sex hormones or differences in brain structure and function (Halpern, 1986). The social and psychological explanations often focus on differential socialization processes or the social construction of gender (Chodorow, 1978; Eagly, 1987; Gilligan, 1982; Lorber & Farrell, 1991), different cognitive styles (Messick, 1976), achievement motivation or self-confidence (Lenney, 1981). The educational explanations mostly concern differences in educational experiences (Wernersson, 1977; 1988) and course taking (Chipman & Thomas, 1985; Wice, 1985). Fennema & Sherman (1977a) found that variables associated with the female sex-role influenced the election of mathematical courses among tenthand eleventh grade females.

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://i1.rgstatic.net/publication/337591259_Examining_test_fairness_across_gender_in_a_computerised_reading_test_A_comparison_between_the_Rasch-based_DIF_technique_and_MIMIC/links/5ddf614aa6fdcc2837f05d8b/largepreview.png)

PDF) Examining test fairness across gender in a computerised

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Christina-Cliffordson-2/publication/248941437/figure/tbl3/AS:669088229638202@1536534473929/Estimated-Means-Standard-Deviations-and-Variances-of-Program-Level-Regression_Q320.jpg)

PDF) Differential Prediction of Study Success Across Academic

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://0.academia-photos.com/attachment_thumbnails/57301608/mini_magick20180904-13045-1xcked3.png?1536075911)

(PDF) Postsecondary Peer Cooperative Learning Programs

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://i1.rgstatic.net/publication/342928174_Examining_the_Fairness_of_Language_Test_Across_Gender_with_IRT-based_Differential_Item_and_Test_Functioning_Methods/links/6012c47c299bf1b33e2f2e12/largepreview.png)

PDF) Examining the Fairness of Language Test Across Gender with

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://i1.rgstatic.net/publication/289963455_Retesting_in_selection_A_meta-analysis_of_coaching_and_practice_effects_for_tests_of_cognitive_ability/links/5f47acf3a6fdcc14c5cef62e/largepreview.png)

PDF) Retesting in selection: A meta-analysis of coaching and

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://d3i71xaburhd42.cloudfront.net/e0d6e9c342a7788a7bde5112d6f792a1ab75b375/11-Figure4-1.png)

PDF] Subject Tests for SAT I: Reasoning Test: Impact on Admitted

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://d3i71xaburhd42.cloudfront.net/bc4eb015c018dd365e4e2327777ecd39b746cd1e/14-Figure2-1.png)

PDF] The Swedish scholastic assessment test (SweSAT) : Development

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://imgv2-2-f.scribdassets.com/img/document/348662825/original/34010d44b0/1699478219?v=1)

Cognitive Abilities and Educational Outcomes, PDF

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://ars.els-cdn.com/content/image/1-s2.0-S027277571930024X-gr1.jpg)

The impact of grade inflation on higher education enrolment and

![PDF] Who takes the Swedish scholastic aptitude test? A study of differential selection to the SweSAT in relation to gender and ability](https://d3i71xaburhd42.cloudfront.net/e0d6e9c342a7788a7bde5112d6f792a1ab75b375/8-Table1-1.png)

PDF] Subject Tests for SAT I: Reasoning Test: Impact on Admitted

de

por adulto (o preço varia de acordo com o tamanho do grupo)